What the Golden Girls taught me about the power of being a friend

Some golden words of wisdom from everyone’s favourite TV foursome.

I was sent to a new school in the middle of Grade 2. For a shy boy who was terrible at making friends, it wasn’t easy.

At break I sat on a bench, eating tear-stained sarmies, watching the other children squeal with laughter as they chased each other.

After a few weeks of loneliness, a boy came up to me.

“Do you want to be my best friend?” he asked.

I nodded.

That nod sealed the deal. I had a best friend, David.

David and I remained best friends, sharing adventures and misadventures, joys and heartache, until he left South Africa when we were teenagers.

Not long after I had gone to the airport to bid him farewell, I watched an episode of The Golden Girls.

I had a David-sized lump in my throat when the show’s theme music played.

The Golden Girls was about four women living together and experiencing the exhilaration and angst of their golden years. But more than that, it revealed the power of friendship.

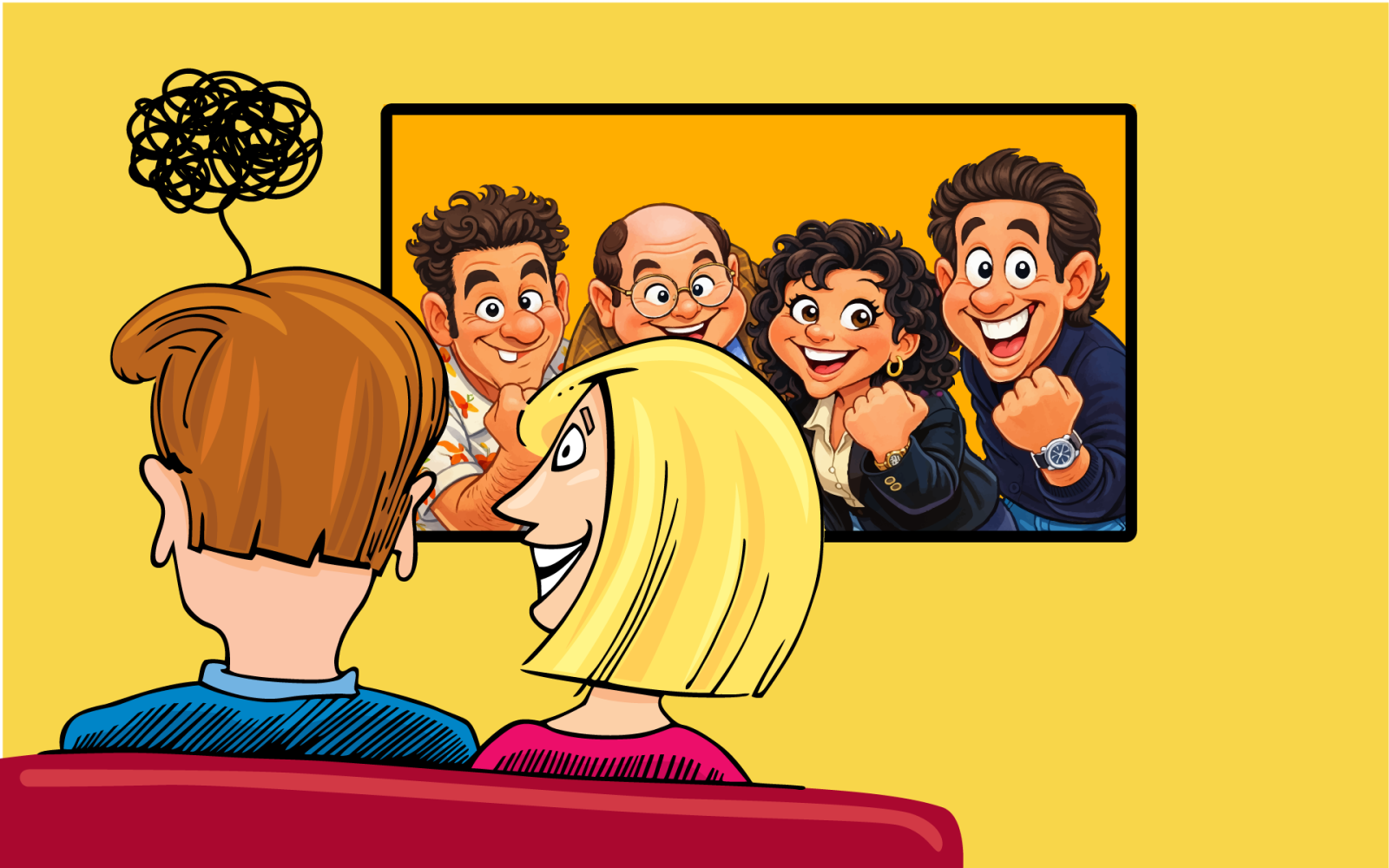

The Golden Girls is just one of a long list of popular sitcoms that centre on friendships. Cheers, Sex and the City, The Big Bang Theory, Seinfeld and, of course, the BFF of all friend shows, Friends.

Our social relationships impact every aspect of our lives. As psychologists remind us, our connections with other people are at the heart of what it means to be human.

Lydia Denworth, author of Friendship: The Evolution, Biology, and Extraordinary Power of Life’s Fundamental Bond, describes friends as a force of good, because they help us find purpose and meaning.

We know social interactions benefit us psychologically. What’s not as well known is that good friends can also improve our physical wellbeing.

Scientists have spent decades researching what kind of impact quality friendships have on our health and how social connections benefit our lives. It’s a lot.

Brigham Young University researchers conducted a meta-analysis study that tracked more than 300,000 participants. The conclusion: the influence of social relationships on risk for mortality is comparable with other well-established risk factors.

To put it in non-scientific terms: We get by with a little help from our friends.

The study found that having a flourishing social life could boost longevity.

Other studies have linked social isolation to raised levels of stress hormones and inflammation, which in turn can increase the risk of heart disease.

It also elevates blood pressure, puts lonely people more at risk of getting cancer, arthritis, Type 2 diabetes and dementia.

Having long-term friendships helps our memories stay sharper for longer.

Friends come with benefits. Immune-boosting benefits.

In his Pittsburgh Common Cold Study, Sheldon Cohen, a psychology professor at Carnegie Mellon University, found that people with strong friendships are less likely to develop and spread the common cold.

But do you know what people who have high-quality relationships are likely to spread?

Happiness, that’s what.

Nicholas Christakis, a Harvard Medical School professor, has found that having a cheerful close friend increases the probability that you’ll be cheerful too.

In fact, friend happiness is contagious. It triggers a cheerful chain reaction that spreads from friend to friend to friend’s friends and so on.

What keeps us happy and healthy as we go through life? That’s the question at the heart of a Harvard study on happiness that began in 1939.

The answer, the study found, is not fame or fortune, but another F-word — friends.

“Taking care of your body is important,” says study director, Professor Robert Waldinger, “but tending to your relationships is a form of self-care too. That, I think, is the revelation.”

Friendships create a sense of safety.

A study in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health found that regular social interactions may boost your self-esteem and reduce anxiety and stress, and provide a buffer against depression.

In their meta-analysis study, the Brigham Young University researchers urged health professionals to take social relationships as seriously as other risk factors that affect mortality, such as smoking, drinking, and obesity.

So, the next time you consult a doctor for some medical advice, don’t be surprised when you’re told: “Make two friends and call me in the morning.”

I haven’t seen David since he left the country three decades ago. We’ve reconnected on social media, and I quietly celebrate his successes and triumphs from the sidelines.

David taught me about the value of friendship, and how important it is to have a close bond with someone who you know is there for you (and they know you’re there for them).

After he left the country, I became the person asking people to be my friend, because life is better when you’re surrounded by close friends, and there’s science to prove it.

So, David, thank you for being a friend.